Knowing that my latest book is about murder and gender – or, more specifically, about a particular narrative of modern identity and individuality that has made possible the figure of the Western “recreational murderer” – lots of people have drawn my attention to the recent case of Joanna Dennehy.

Knowing that my latest book is about murder and gender – or, more specifically, about a particular narrative of modern identity and individuality that has made possible the figure of the Western “recreational murderer” – lots of people have drawn my attention to the recent case of Joanna Dennehy.

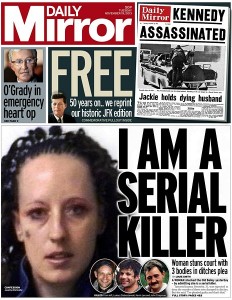

Dennehy is a 32-year-old British woman who enlisted her apparently enthralled male lovers, Gary Stretch and Leslie Layton, to be her accomplices in the murders of three men, Lukasz Slaboszewski, Kevin Lee, and John Chapman. (See here.) Dennehy’s documented taste for sadomasochistic sexual practices (see here) has added to the frenzied media interest in the case, and has led to the production of some dubious psychiatric diagnoses, which I plan to write about elsewhere. Dennehy is both statistically unusual and discursively rare in being described as a female recreational killer whose apparent motives for committing her crimes were sexual sadism and thrill-seeking.

Yet, one Facebook interlocutor recently pointed out to me that cases of women committing multiple killings similar to Dennehy’s – typically “masculine crimes” – seem to be on the rise and are certainly in the public eye at the moment. (The case of the “Craig’s List Killer”, 19-year-old Miranda Barbour, springs immediately to mind.) While two do not a trend make, it is interesting to wonder if the Zeitgeist is in some way enabling the emergence of a new kind of female murderer. My approach to this problem, then, is historically and culturally, rather than psychologically, oriented. (I am not interested in individual psychological motivation, but in the social-historical conditions that produce the figure of the murderer as bizarrely aspirational, and that make it available to certain classes of person, in certain situational contexts.)

In The Subject of Murder I argue that, in modern Western culture, the murderer has the status of exceptional individual. This goes back to the Romantic/ Decadent idea of the “artist-criminal”, in whom creativity and destructivity are two sides of the same coin. Of course this idealized, semi-fictional figure of potency is implicitly white and male (though his sexual identity is often portrayed as fluid, alternating between heterosexual hyper-masculinity and an ambivalent homoeroticism). Thomas De Quincey, Oscar Wilde, and Jean Genet have all waxed lyrical about the genius-murderer and the trope of murder-as-art in literary and aesthetic-philosophical writing.

In our contemporary culture, this grandiose murderous exceptionality takes the form of celebrity, as David Schmid has compellingly argued in his 2005 book, Natural Born Celebrities. “Murderer” is a celebrity identity, as seen in the wealth of press attention that is brought to bear on infamous killers, and the aura that accrues to people, and even to things, close to those killers. The phenomenon of “murderabilia”, objects and artworks created or previously owned by infamous killers that have a highly collectible status, is one manifestation of this. The attention-seeking behaviour of many serial killers reinforces their visibility. Many killers at large have sent taunting letters to the police and press, such as David Berkowitz, the “Son of Sam”, active in the USA in the 1970s. In other cases, such as that of the Yorkshire Ripper (Peter Sutcliffe, in the UK), letters have been sent by others pretending to be the murderer, increasing the visibility of the case and speculation around the identity of the killer. And, tellingly, this was a trend popularized by the first “celebrity serial killer” at the historical moment of efflorescence of the popular press – the still-unidentified Victorian murderer, Jack the Ripper. (That the mass press and the serial killer are products of the same age is far from a coincidence.) Once caught and imprisoned, notorious killers can also keep up a high media profile. “Moors Murderer” Ian Brady’s recent appeal to be transferred from high security mental hospital to prison, his claim that he had revealed the whereabouts of a victim’s body in a letter to his mental health advocate, and his much discussed hunger strike, are good examples of this. (See my post on Brady here.)

It will be noted that all of the names above are male. It is not, of course, the case that there have historically been no female killers, but media and culture have not tended to represent murderesses in the same (ambivalently heroic) terms that they have used to represent men who kill – and that men who kill can then take up as a badge of identity. Prominent female killers of the past century have included Myra Hindley, Rosemary West, and Aileen Wuornos, all of whom killed violently, and (in the cases of the first two at least), for sexual motives. However, the first two names are notable for being one half of celebrity murderous heterosexual couples (Myra and Ian; Rose and Fred), and both women were vilified in much stronger terms than their male partners, whose sexual violence was, in each case, seen as an aberrant but intelligible extension of socially sanctioned masculinity. Similarly, Wuornos, as that very rare type of killer, a lesbian lone-wolf, stalking her male victims under the guise of selling sexual services, attracted vitriol and hatred from press and public, and an extremely harsh punishment relative to male perpetrators of similar crimes. (She received multiple death sentences, despite the defense presenting mitigating evidence of childhood sexual abuse, and mental illness.) Some coverage of Joanna Dennehy’s case has discussed the difficulty society has in accepting violent women, and has posited that Dennehy, as a sexually adventurous, hedonistic spree-killer, presents particular problems to the codes of representation that are available for describing women who kill. (See especially Elizabeth Yardley’s intelligent commentary in The Guardian. Avoid the comments if you wish to retain any sort of faith in the critical thinking skills of the reading public.)

Can we really argue, then, that Joanne Dennehy is a representative of a new type of female murderous subject, who employs the same grandiose self-stylization and press attention-seeking tactics as her male counterparts? There is certainly evidence that Dennehy boasted she was seeking to become a “famous serial killer” at least two years before committing the triple murder. (See here.) And, she described herself, while on the run, as “Bonnie” of Bonnie and Clyde, suggesting strong identification with available cultural representations of female criminality. (See here.) Like the Columbine killers, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, who conceived their high-school shootings in advance as a media spectacle, and like Stephen Griffiths, the Bradford “Crossbow Cannibal”, who was a criminology student fascinated by the figure of the serial killer, Dennehy was undoubtedly tapping into the same available cultural repository of criminal myth-making as many male killers before her.

So where does Dennehy’s type of murderous subjectivity come from? We might conclude by drawing a parallel with the ways in which what is known as “raunch culture” has been embraced by some women as a (dubious) badge of empowerment in a post-feminist age. This idea was introduced by Ariel Levy in Female Chauvinist Pigs (2005). Levy argues that the rise of the FCP, who is just as likely to appear in a strip club in the role of patron as of performer, has contributed to the erasure of the feminist struggle and to making invisible intersecting, class-based, power imbalances. Female Chauvinist Pig culture co-opts a very narrow definition of “power”, based on aping valorized, typically “masculine” behaviours and roles, and showing that (some) women can access and benefit from those roles too. As Levy points out, these exceptional women achieve their agency in contradistinction to, and at the expense of, other “lesser” women, rather than by raising up the collectivity of women as a group. Perhaps, by analogy, a form of violent, antisocial self-stylization is becoming more available to those women who find themselves on the margins of social acceptability, and who seek to make a name for themselves in a culture obsessed with fame and exposure. It may be that the search for infamy offered by the label of “serial killer” is increasingly the antisocial, shadow alternative to seeking pop fame on The X Factor, or the hyper-visibility of glamor-modeling, for socially disenfranchised women of the twenty-first century, who see individualistic forms of male violence celebrated, and who want a piece of that celebrity for themselves.

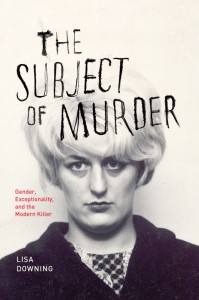

My book, The Subject of Murder: Gender, Exceptionality, and the Modern Killer, which took me six years to write, and which has been in production for over 12 months with Chicago University Press, is finally available for pre-order, though it won’t be in the world until next year. It is a relative snip at $25 / £15.

My book, The Subject of Murder: Gender, Exceptionality, and the Modern Killer, which took me six years to write, and which has been in production for over 12 months with Chicago University Press, is finally available for pre-order, though it won’t be in the world until next year. It is a relative snip at $25 / £15. Shulamith Firestone, radical feminist writer, died on 28th August 2012, aged 67. She is best known as the author of the groundbreaking polemic,

Shulamith Firestone, radical feminist writer, died on 28th August 2012, aged 67. She is best known as the author of the groundbreaking polemic,